ABOUT LUNA PARK

A Brief History of Luna Park

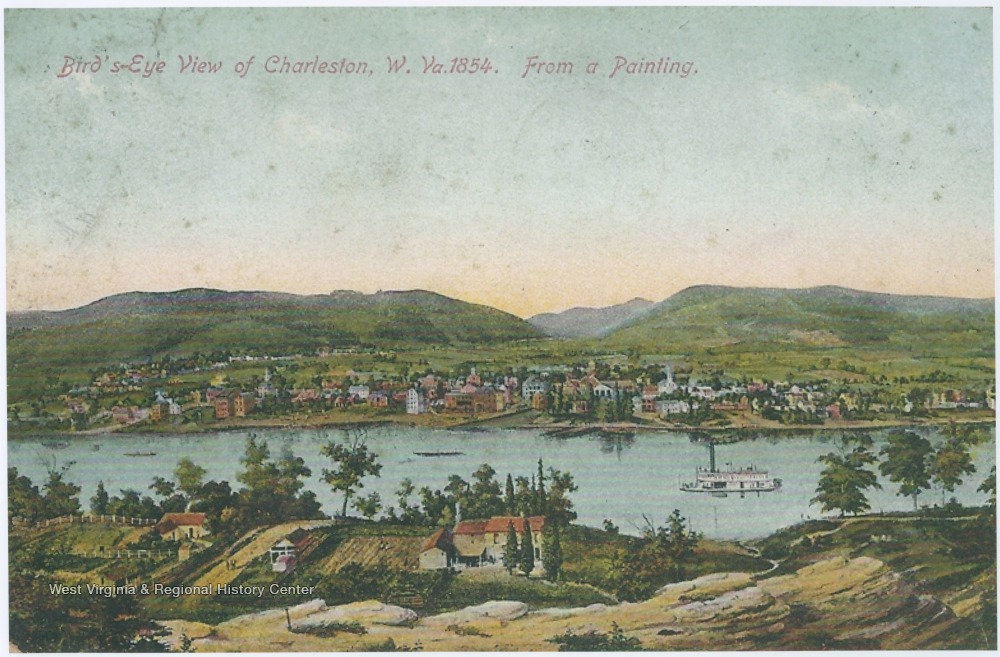

What we now know as the Luna Park Historic District was once sparsely populated agricultural land and the location of Glenwood Estate, a nineteenth century farm run by slave labor, similar but smaller in scale to southern slave plantations.

The transition from agriculture to industry for much of the West Side began with the construction of bridges over the Elk River in 1873 and again in 1883. Elk City, then an independent municipality, became the heart of commerce west of the Elk and included brick yards, saw mills, and furniture factories.

Then in 1905, the Kelly Axe and Tool Company settled near present-day Patrick Street, covering 50 acres and employing nearly 1,000 people. This steady economic growth continued throughout much of the early twentieth century and Charleston’s population grew accordingly. That population needed housing and entertainment, and this set the stage for the development of Luna Park Historic District for decades to come.

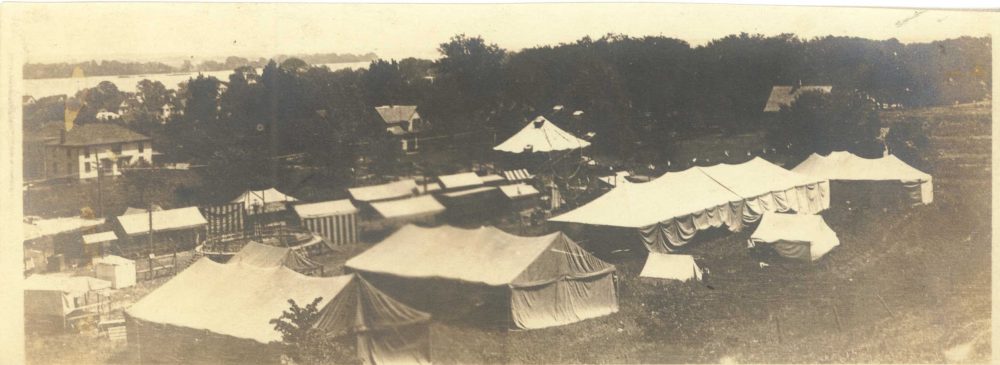

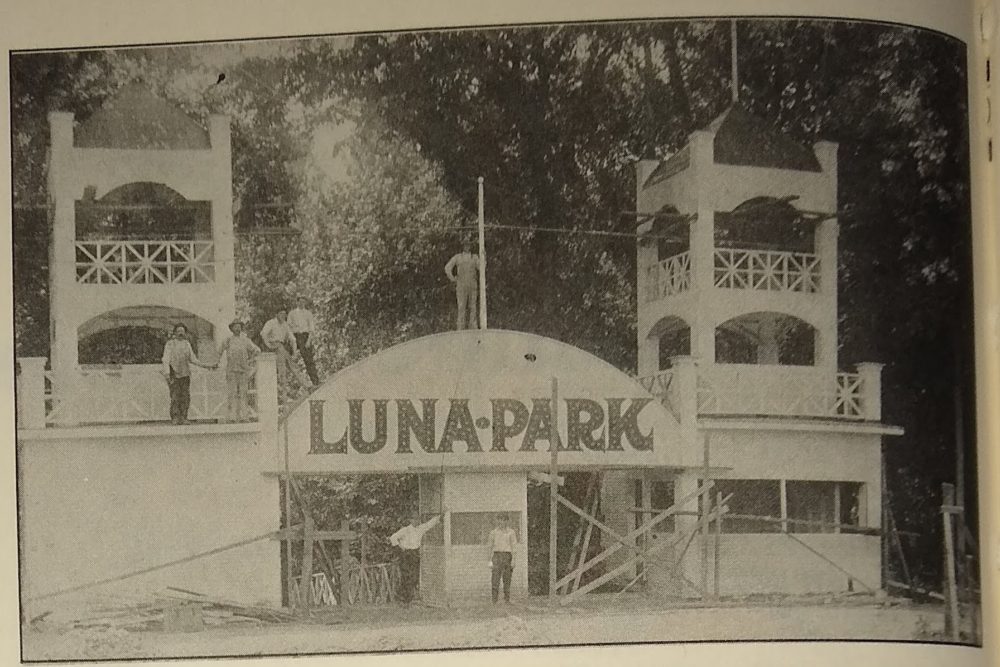

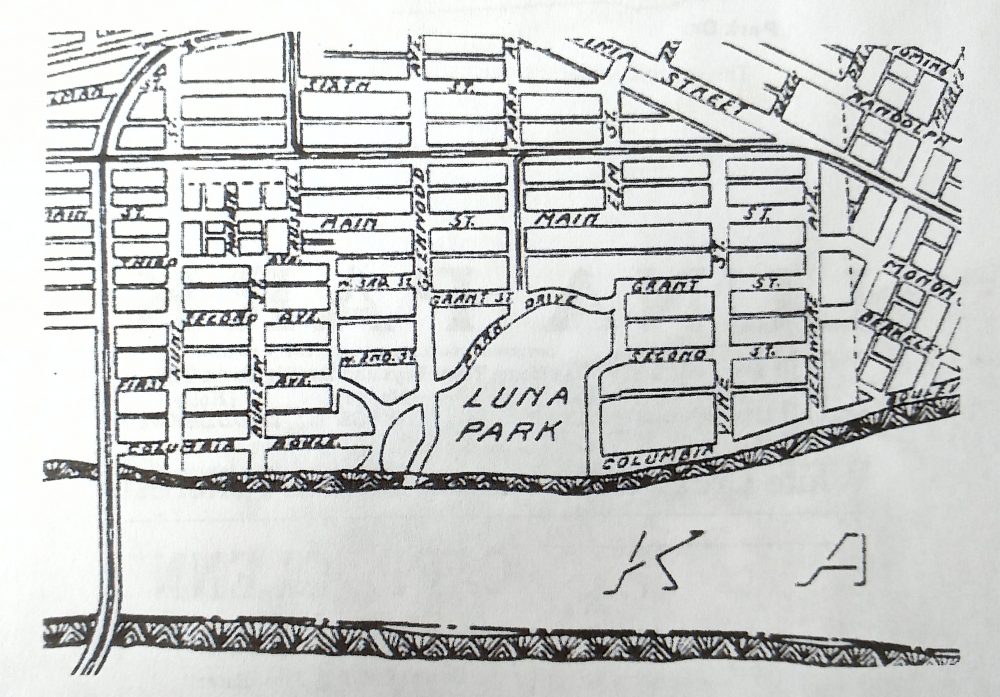

Maps of the area from 1912 depict Glenwood Park, a golf course situated on rolling marshy ground. But construction began that same year on the community amusement park for which the district is named.

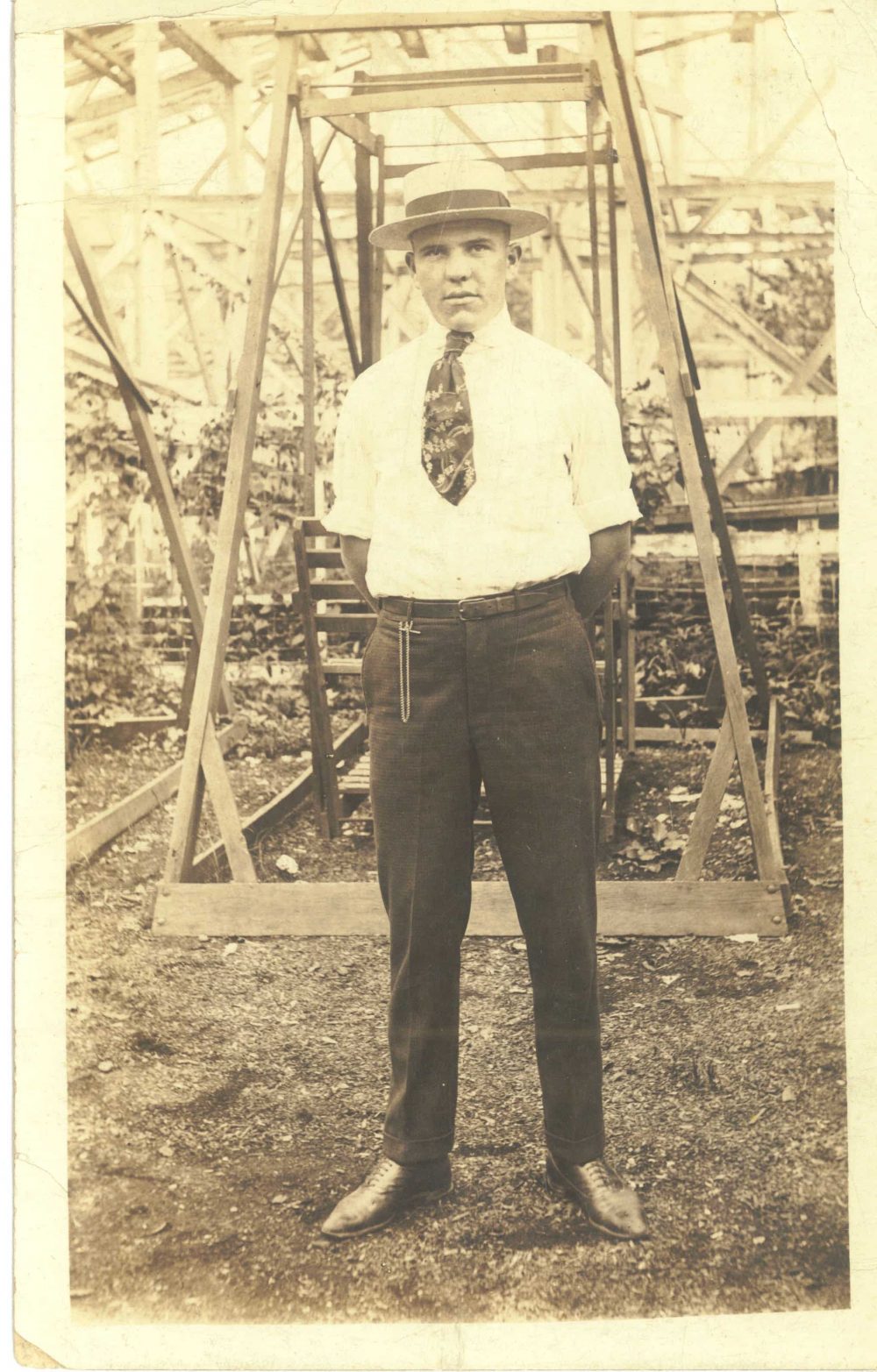

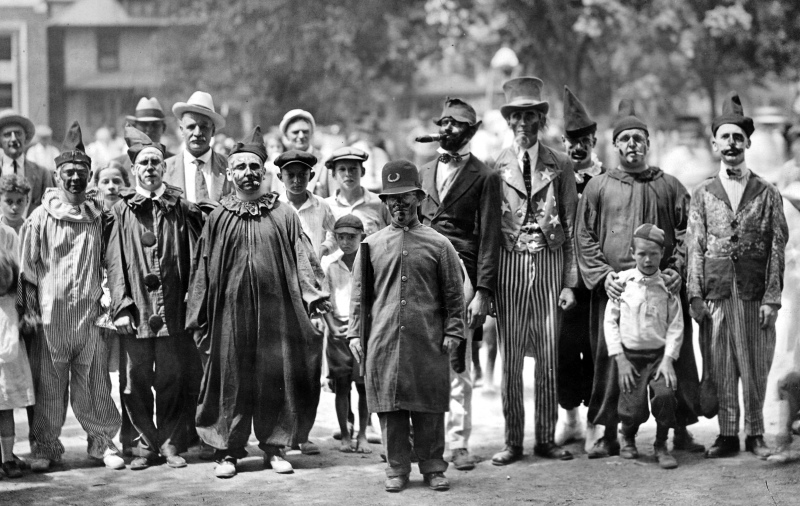

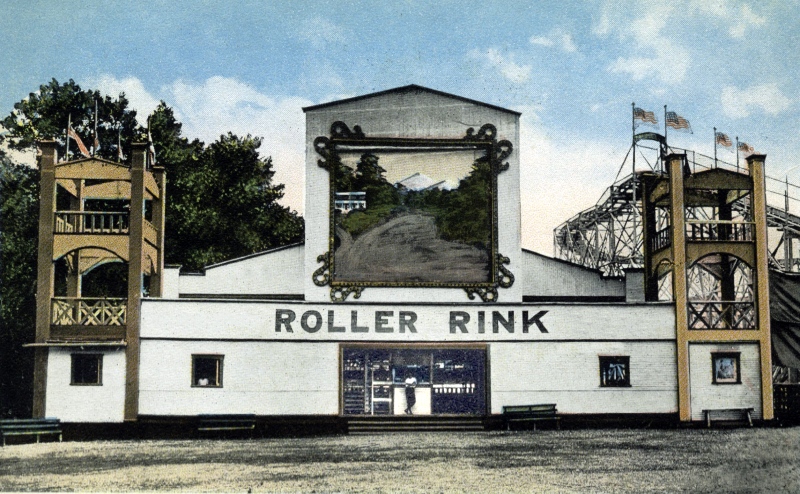

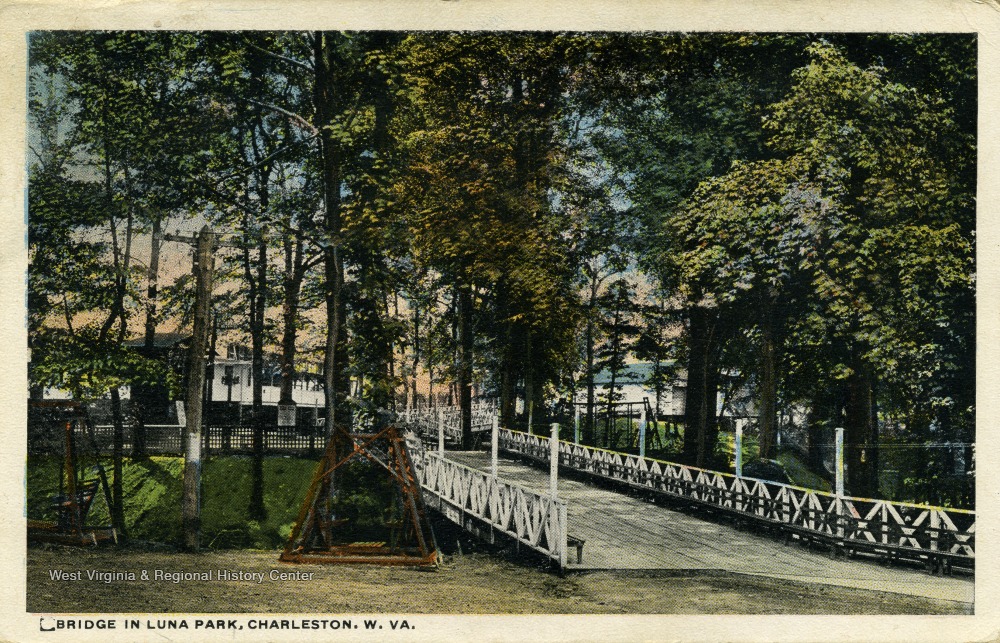

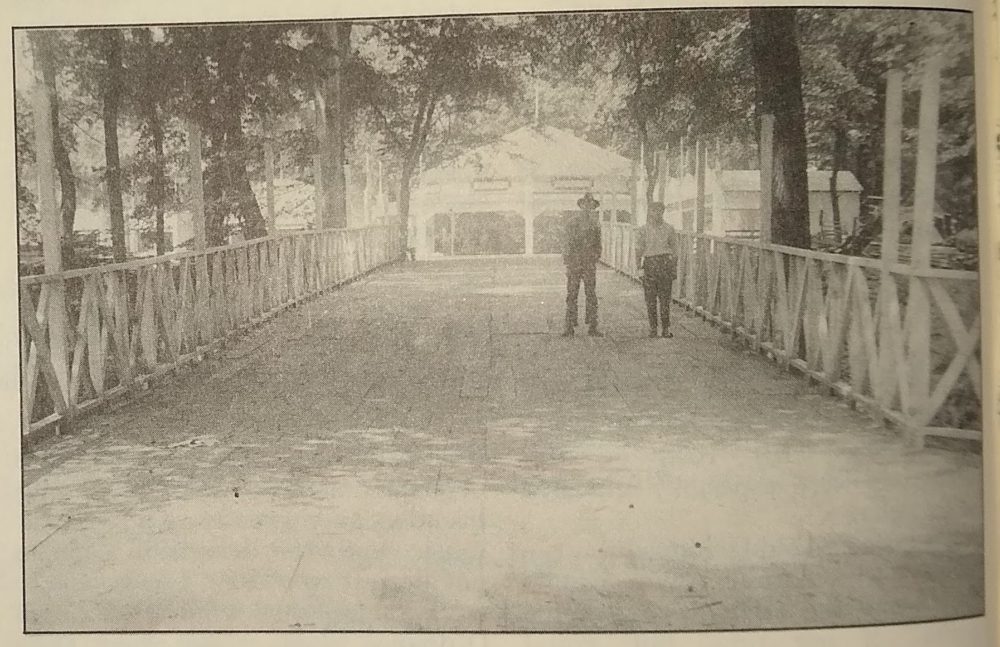

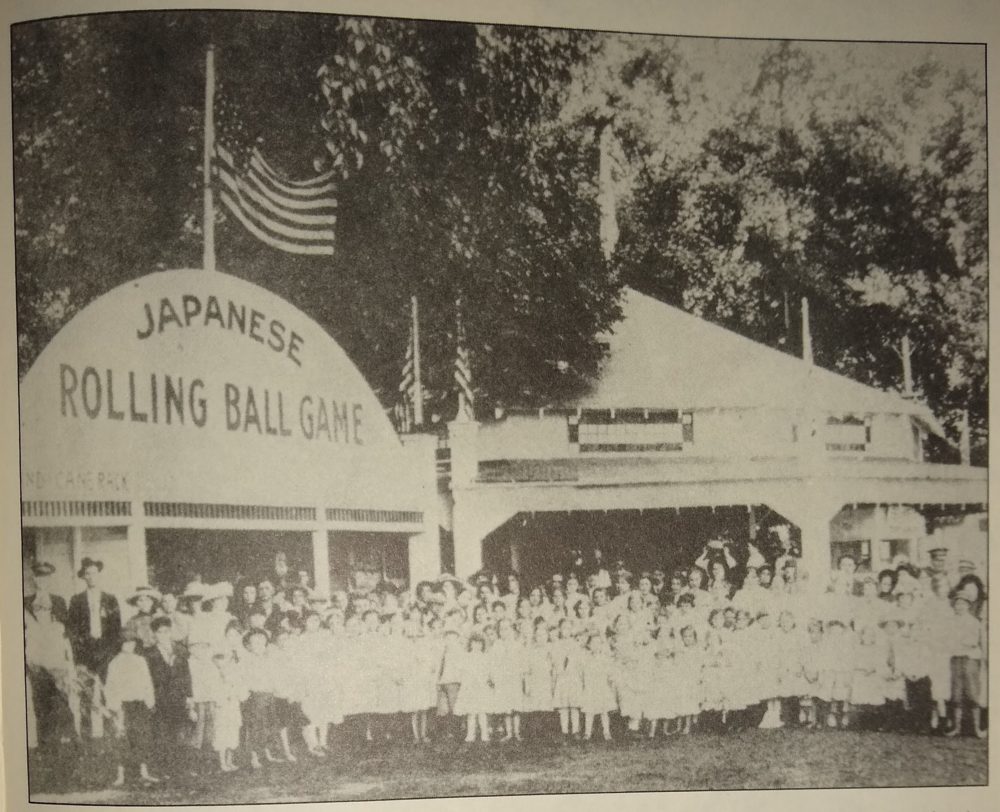

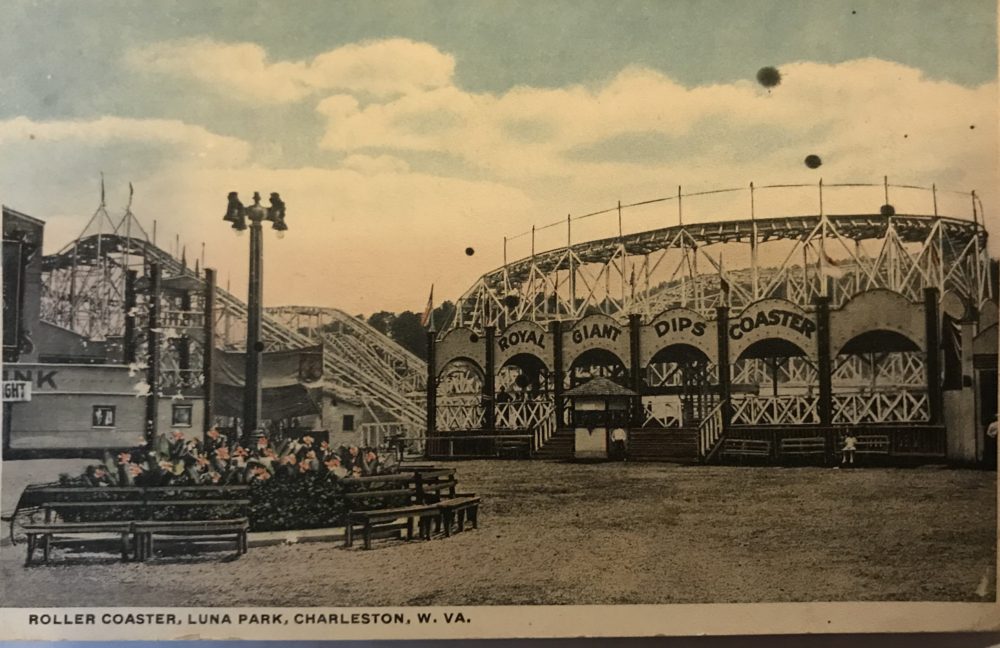

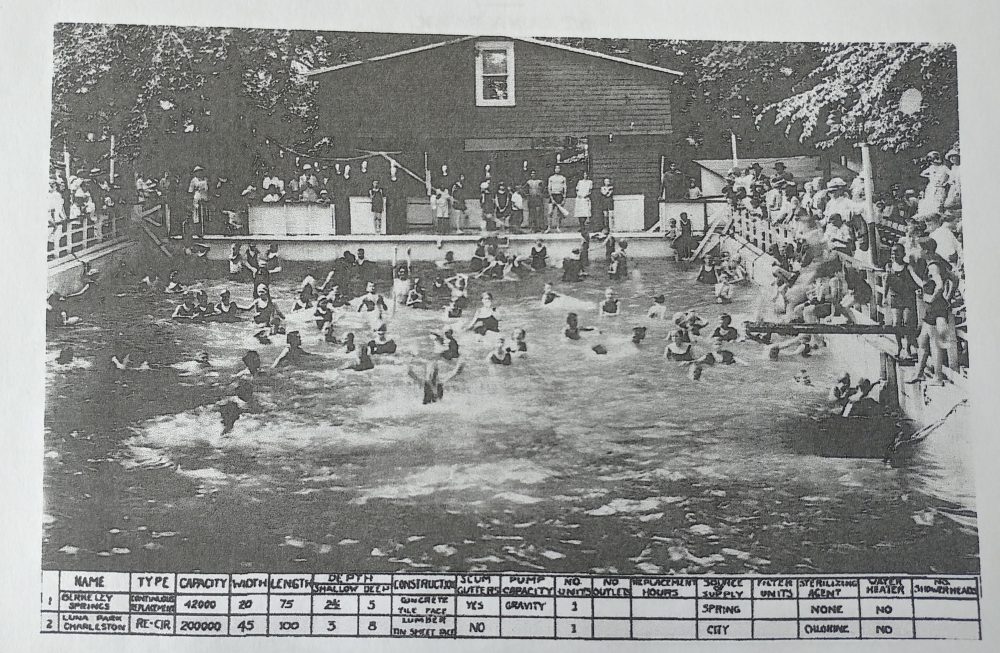

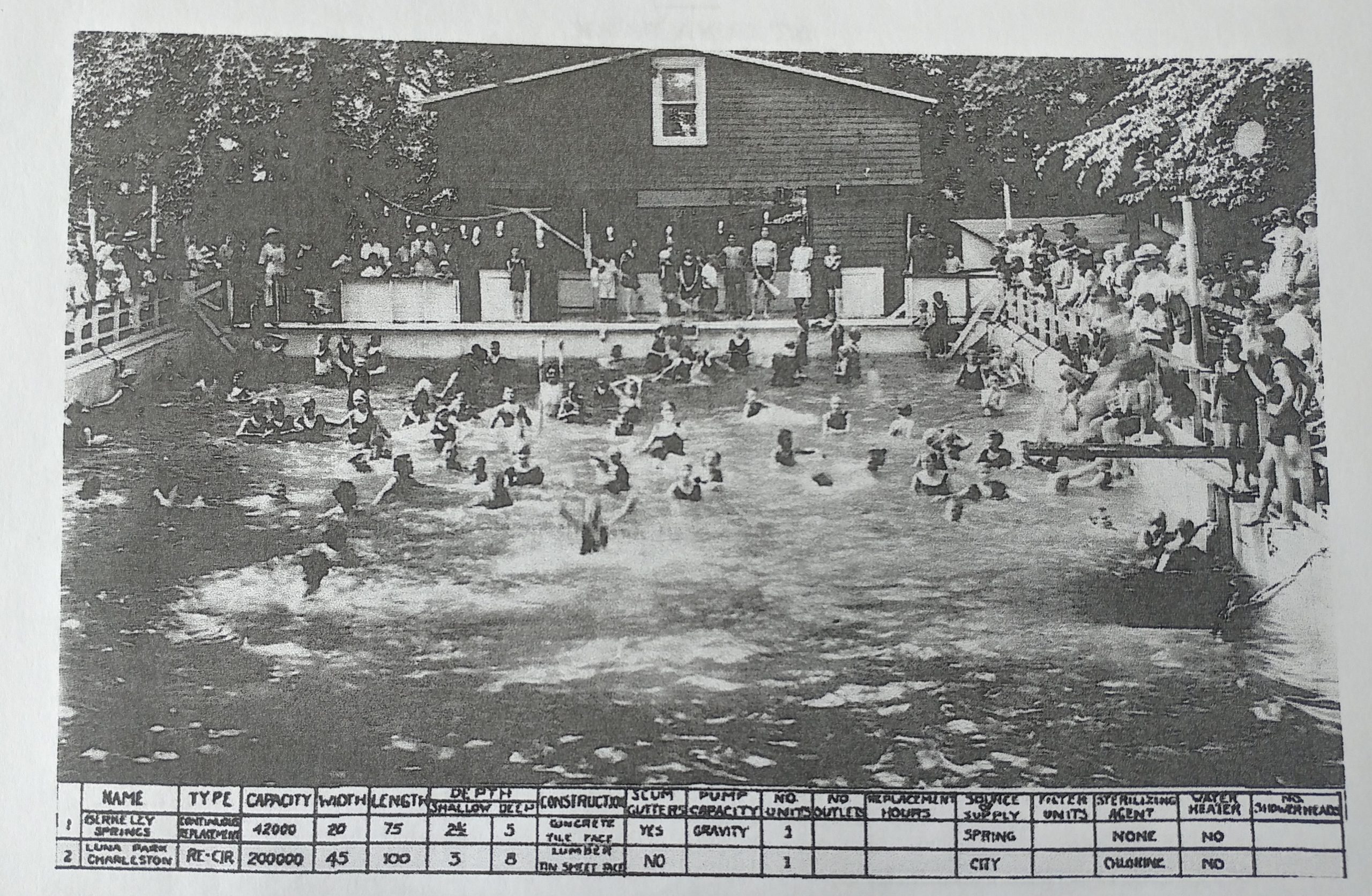

Charleston’s Luna Park, opened in 1913, was one of a chain of 44 parks created by inventor-designer-builder Frederick Ingersoll. The park was built amid streams, bridges, and gullies along the meandering walking paths. It offered a complete amusement package, consisting of a series of booths, a dance pavillion, a restaurant and confectionary, a merry-go-round, a shooting gallery, a roller rink, a concrete swimming pool, along with a wooden rollercoaster and a Ferris wheel.

Though no concrete evidence has been discovered, it is presumed that Luna Park excluded African Americans and others as well. This is inferred from few the photos we have of the patrons in the park and the fact that West Virginia was a de facto Jim Crow state during the park’s time.

Luna Park in Charleston operated until 1923, when a worker’s blow torch ignited a fire in the pool house. The fire quickly spread, and Luna Park was a total loss. Evidence of Luna Park is present in the district even today. Park Drive and Park Avenue are aptly named, and the curve of Lovell Drive and Grant Street echos the Luna Park boundary.

It was after the fire in 1923 that the Luna Park Land Company cleared the site and began developing plans for a 95-lot residential subdivision. The lots created were long and narrow, leaving little room for side yards. In most cases, buyers agreed to build homes valued at $3,500 or more and to situate those homes no closer than 15 ft to the curb.

Marketed as “Charleston’s Beauty Spot,” the new subdivision carried with it other building controls, most notably including a racial restriction. Attached to the deeds as a covenant running with the land was language prohibiting the lease or sale of the properties to any person of color. Such restrictions were common practice and legal nationwide until the Civil Rights Movement. While discrimination in housing was outlawed with the Fair Housing Act of 1968, racial discrimination lasted decades beyond. This legacy is reflected today on Charleston’s West Side.

Even the architect John C. Norman Sr, the first registered Black architect in West Virginia, had built homes in the neighborhood though he and his family could not own a home there. They would build a Craftsman-style home on the West Side outside and nearby Luna Park at 1118 Second Avenue, which still stands.

Slowly homes and schools became integrated in the 60s and 70s. On an individual basis, homes were sold to Blacks and other people of color until eventually the deed restrictions were systematically lifted entirely.

The demolition of the Triangle District as a part of an urban renewal project in 1974 accelerated housing integration as many African Americans were put out of their businesses and homes in this primarily Black district.